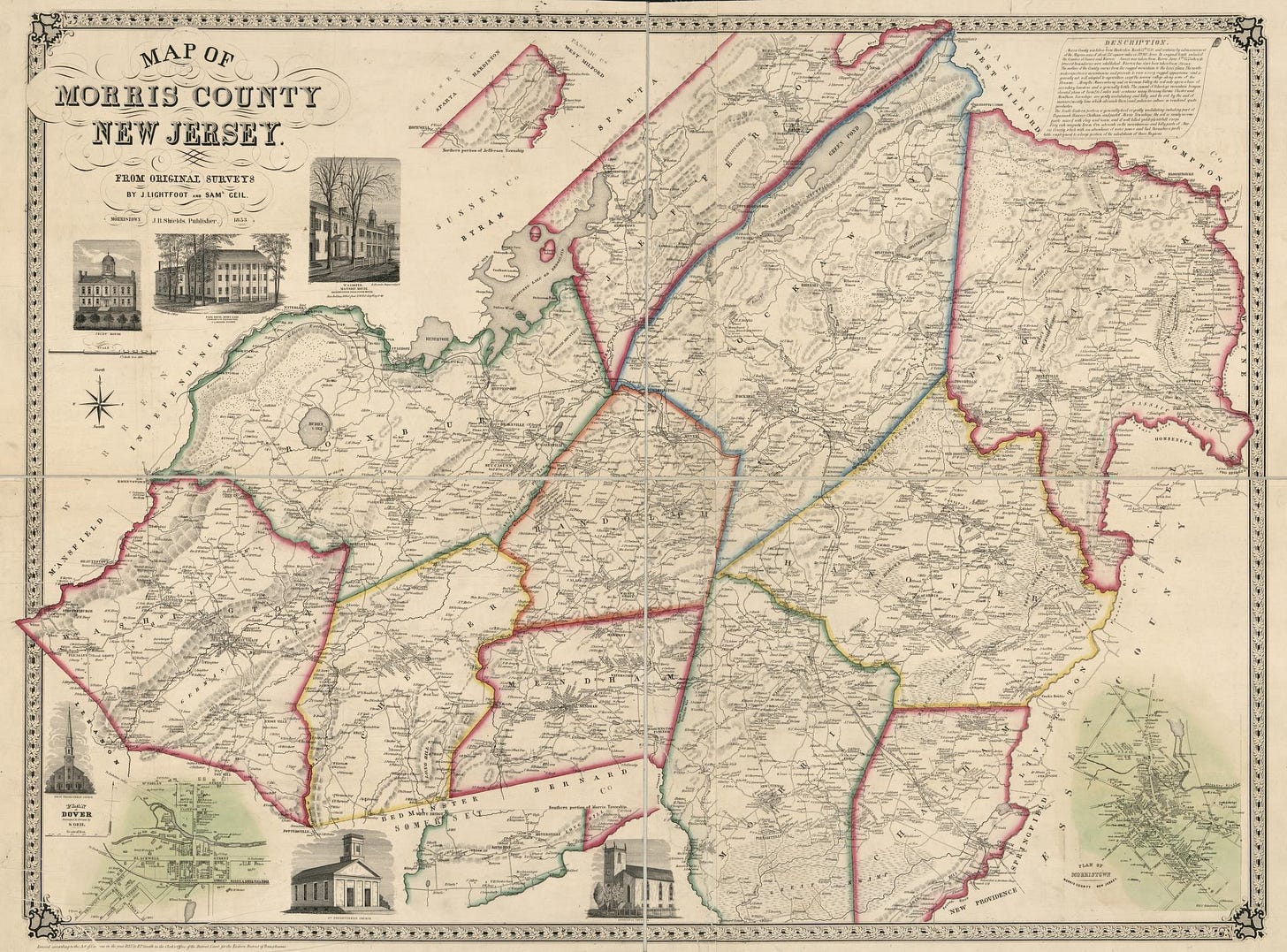

This week I came across a fascinating story that took place in Morris County in the late 18th century. It involves a murder and a highway.

But before we get to that, a little bit about how we choose stories for Hometown History.

How I got here:

Some of the best stories I’ve read about New Jersey aren’t readily available. They’re often in books written by local authors telling stories they’ve heard first or second hand from someone else. Often, if you try hard enough, you can trace a particular story back to the original record of it (something we call a “primary source”). In reality, these primary sources are the only way to ensure we know the true details behind something that happened once upon a time. If you can’t find a primary source, you may be able to corroborate multiple tellings of the story, as long as they aren’t referencing each other, in which case we’re back to where we started again.

In Season 1 of Hometown History we came across so many stories that we just couldn’t quite verify. It was frustrating! Why didn’t more people write stuff that happened down? We decided that part of our mission was to be as accurate and transparent with historical facts as it was possible to be. We leaned into stories we could back up with certainty, and made it clear when some detail or another may have been more legend than fact.

I picked up this slim volume from the library this week called Historic Morris County. It looks to be a small batch print from the 1940’s, perhaps published as a gift or public gesture by The National Iron Bank of Morristown (something we should put a pin in to discuss later). Long story short, there is no proper author or bibliography. No way to tell or check that what this little volume contains is accurate. And yet these stories are vivid and compelling; the language is rich and old-fashioned. And despite questions about its provenance, I’m dying (Ha!) to share one of these stories here with you all.

The short version of the story:

We all know that Morristown was the setting of some historic moments from the American Revolution. But what was life like in pre-revolutionary Morristown, before Washington and war burnished it’s reputation? According to the author of Historic Morris County:

“Most people were poor, a few well-to-do. All were industrious and God-fearing. A few were hard drinkers, and too many of them, high and low, were superstitious. Iron was the lodestar of the community and everybody was in iron directly or otherwise, writer he be farmer, merchant or craftsman. Small meeting houses were fully attended, twice on Sunday and two or three times during the week.

“Much, if not all, of the community business was transacted over mug or cup, and some of the most momentous decisions in the nation's behalf were sealed in enthusiasm derived from the glow of a toddy consumed in some tavern in Morristown.”

It would be more than a decade or two before America would codify her rule of law. In the meantime, justice in Morristown was swiftly delivered in whatever way the townspeople saw fit.

For example, legend has it that a schoolmaster named Brakeman and a small peddler met by chance one night in a Morristown tavern. They left the tavern together and were not seen again until the next morning when a farmer boy located the peddlers body in a nearby forest. The schoolmaster was rounded up and brought to trial. Seems kosher, right? Except that at the time in Morristown the judgment of someone’s guilt or innocence came down to a test of “presence and touch”. How was it administered? You bring the suspect to the scene of the crime and have them touch the body or some object the body has touched. If blood gushes from the object, the accused is guilty. If nothing happens, the suspect is pronounced innocent.

So the schoolmaster Brakeman was found to be not guilty by virtue of the fact that this test is ridiculous. Delighted by the outcome, the story goes that Brakeman forgot himself and confessed to the murder. He was hanged that afternoon and justice had been served.

But that’s not the end of the story. The author of Historic Morris County goes on to say that:

“For years, William Wood, on whose property the murder occurred, could neither sell nor rent any of his land, as everyone believed the whole region “haunted.”

Finally Wood offered ten acres of land and a new log house, built upon the murder spot, to anyone who would occupy it. A practical man named Ebenezer Jayne took up the odder and turned the dwelling into an emporium for cakes and ale and named it Brakeman’s Hotel, honoring the deceased schoolmaster.The storyteller goes on to say that:

“Jayne’s stand so flourished that other settlers, anxious to get in on the good luck, bought all of Wood’s property and moved father and father out until a new road had to be cut to serve them.”

The road today passes through and connects Morristown to Dover.

What a tale, right? I love a good “how this infrastructure was made” story, especially if it involves a ghost.

Final thoughts:

Just because we don’t know who wrote this story down or where they heard it, doesn’t mean we can’t try to find out if its true for ourselves. The point is, history seems to work just like our memories. If we don’t record them accurately, their truth may be lost to time. You might recall a story differently the next time you tell it. And then next time and the next and the next. Until it is just a shadow (or a ghost?) of what really happened.

A shadow of history is still better than no history at all, and I’m happy that someone at the National Iron Bank of Morristown was prescient enough to print this little booklet. Hometown History will keep doing it’s best to ensure that New Jersey history is preserved.

Links:

Historic Morris County, The National Iron Bank of Morristown, 1942, pg 6-7 https://www.amazon.com/Historic-beginning-discovery-Morristown-vicinity/dp/B001B1TEJA

Fascinating! The process leading to the hanging does sound apocryphal, or, if not, worth a deeper dive.